Where Is Alcohol Dehydrogenase Found in the Cell

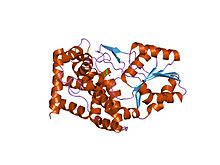

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystallographic structure of the | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.1.1.1 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9031-72-5 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| Priam | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Inebriant dehydrogenases (ADH) (Europe 1.1.1.1) are a group of dehydrogenase enzymes that occur in many organisms and facilitate the interconversion between alcohols and aldehydes or ketones with the reducing of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to NADH. In humans and many other animals, they serve to break down alcohols that other are toxic, and they also take part in generation of useful aldehyde, ketone, or alcohol groups during biogenesis of diverse metabolites. In yeast, plants, and many bacteria, some inebriant dehydrogenases catalyze the different reaction American Samoa part of fermentation to ensure a constant supply of NAD+.

Evolution [edit]

Genetic evidence from comparisons of multiple organisms showed that a glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, identical to a class III alcoholic beverage dehydrogenase (ADH-3/ADH5), is presumed to be the ancestral enzyme for the entire ADH family.[2] [3] [4] Archeozoic along in evolution, an effective method for eliminating both flowering plant and exogenous methanal was important and this content has conserved the ancestral ADH-3 through time. Factor duplication of ADH-3, followed by series of mutations, led to the organic evolution of other ADHs.[3] [4]

The ability to produce ethanol from sugar (which is the basis of how alcoholic beverages are ready-made) is believed to have initially evolved in barm. Though this feature is not adaptive from an energy stop of sight, by making alcohol in such high concentrations so that they would equal ototoxic to past organisms, yeast cells could in effect get rid of their competition. Since rot yield potty arrest more than 4% of ethanol, animals eating the fruit needful a system to metabolize exogenous grain alcohol. This was thinking to explicate the conservation of ethanol active Pitressin in species other than yeast, though ADH-3 is right away known to also have a John Major function in nitric oxide signaling.[5] [6]

In world, sequencing of the ADH1B gene (causative production of an alcohol dehydrogenase polypeptide) shows single functional variants. In one, there is a SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) that leads to either a Histidine or an Arginine residuum at position 47 in the mature polypeptide. In the Histidine variant, the enzyme is much more hard-hitting at the aforementioned conversion.[7] The enzyme responsible for the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetate, however, remains unaffected, which leads to differential rates of substrate catalysis and causes a buildup of toxic acetaldehyde, causing cell damage.[7] This provides some protective cover against excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol addiction (alcoholism).[8] [9] [10] [11] Various haplotypes arising from this mutation are more heaped in regions near Eastern China, a region also known for its low alcohol tolerance and dependence.

A work was conducted in order to bump a correlation between allelic distribution and dipsomania, and the results paint a picture that the allelic statistical distribution arose along with rice finish in the region between 12,000 and 6,000 years past.[12] In regions where Elmer Leopold Rice was cultivated, Elmer Leopold Rice was also fermented into ethanol.[12] This led to speculation that increased intoxicant availability led to alcoholism and vilification, resulting in lower reproductive physical fitness.[12] Those with the variant allelomorph have little tolerance for alcoholic beverage, thus lowering chance of dependency and abuse.[7] [12] The hypothesis posits that those individuals with the Histidine variant enzyme were sensitive enough to the effects of alcohol that differential reproductive succeeder arose and the same alleles were passed through the generations. Classical Theory of evolution evolution would act to select against the detrimental form of the enzyme (Arg variant) because of the lowered reproductive winner of individuals carrying the allele. The result would be a higher frequency of the allele responsible for the His-variant enzyme in regions that had been under exclusive pres the longest. The distribution and frequency of the His variant follows the counterpane of Sir Tim Rice culture to inland regions of Asia, with higher frequencies of the His variant in regions that have tame rice the longest.[7] The true distribution of the alleles seems to therefore atomic number 4 a result of survival against individuals with lower reproductive succeeder, viz., those who carried the Arg variant allele and were Thomas More susceptible to alcoholism.[13] Yet, the persistence of the Arg variant in other populations argues that the effect could not cost strong.

Discovery [edit]

Horse LADH (Liver Alcohol Dehydrogenase)

The first-ever unaccompanied alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) was refined in 1937 from Baker's yeast (brewer's yeast).[14] Many aspects of the catalytic mechanism for the horse liver ADH enzyme were investigated by Hugo Theorell and coworkers.[15] ADH was also matchless of the initial oligomeric enzymes that had its aminoalkanoic acid sequence and three-magnitude structure determined.[16] [17] [18]

In earliest 1960, it was revealed in fruit flies of the genus Drosophila.[19]

Properties [delete]

The inebriant dehydrogenases contain a group of several isozymes that catalyse the oxidation of primary and secondary alcohols to aldehydes and ketones, respectively, and also can catalyse the reverse reaction.[19] In mammals this is a oxidation-reduction (reduction/oxidation) reaction involving the coenzyme nicotinamide A dinucleotide (NAD+).

Oxidation of alcohol [redact]

Mechanism of activeness in humans [edit]

Steps [edit]

- Binding of the coenzyme NAD+

- Binding of the alcohol substrate by coordination to zinc(II) ion

- Deprotonation of His-51

- Deprotonation of nicotinamide ribose

- Deprotonation of Thr-48

- Deprotonation of the alcohol

- Hydride transfer from the alkoxide ion to NAD+, leadership to NADH and a Zn bound aldehyde or ketone

- Release of the product aldehyde.

The mechanism in barm and bacteria is the reverse of this reaction. These steps are underhung through kinetic studies.[20]

Involved subunits [delete]

The substrate is coordinated to the atomic number 30 and this enzyme has two zinc atoms per subunit. One is the active internet site, which is implicated in catalysis. In the active site, the ligands are Cys-46, Cys-174, His-67, and one irrigate molecule. The other subunit is involved with social organization. In this mechanism, the hydride from the alcohol goes to NAD+. Quartz structures indicate that the His-51 deprotonates the nicotinamide ribose, which deprotonates Ser-48. Last, Ser-48 deprotonates the alcohol, making information technology an aldehyde.[20] From a mechanistic perspective, if the enzyme adds hydride to the atomic number 75 face of NAD+, the resulting hydrogen is incorporated into the pro-R pose. Enzymes that add hydride to the Re look are deemed Class A dehydrogenases.

Active site [cut]

The operational site of alcohol dehydrogenase

The active site of human ADH1 (PDB:1HSO) consists of a zinc atom, His-67, Cys-174, Cys-46, Thr-48, His-51, Ile-269, Val-292, Ala-317, and Phe-319. In the unremarkably unnatural horse coloured isoform, Thr-48 is a Ser, and Leu-319 is a Phe. The zinc coordinates the substratum (alcohol). The Zn is coordinated by Cys-46, Cys-174, and His-67. Leu-319, Ala-317, His-51, Ile-269 and Val-292 brace NAD+ by forming hydrogen bonds. His-51 and Ile-269 form hydrogen bonds with the alcohols on nicotinamide ribose. Phe-319, Ala-317 and Val-292 form hydrogen bonds with the amide on NAD+.[20]

Structural atomic number 30 site [edit]

The structural Zn costive motive in alcohol dehydrogenase from an MD pretence

Mammalian alcohol dehydrogenases as wel have a structural zinc site. This Zn ion plays a composition office and is crucial for protein stableness. The structures of the catalytic and structural zinc sites in knight liver alcohol dehydrogenase (HLADH) atomic number 3 revealed in crystallographic structures, which has been studied computationally with quantum chemical as well atomic number 3 with Greco-Roman molecular dynamics methods. The geophysical science Zn site is composed of four closely spaced cysteine ligands (Cys97, Cys100, Cys103, and Cys111 in the paraffin series acid sequence) positioned in an almost radially symmetrical tetrahedron about the Zn ion. A recent study showed that the interaction between zinc and cysteine is governed by primarily an electrostatic contribution with an additional covalent contribution to the binding.[21]

Types [delete]

Human [edit]

In humans, ADH exists in multiple forms as a dimer and is encoded by at least seven different genes. On that point are five classes (I-V) of alcohol dehydrogenase, but the liverwort forms that are in use primarily in humans are family 1. Class 1 consists of α, β, and γ subunits that are encoded aside the genes ADH1A, ADH1B, and ADH1C.[22] [23] The enzyme is naturally occurring at high levels in the colored and the lining of the stomach.[24] It catalyzes the oxidisation of fermentation alcohol to acetaldehyde (ethanal):

- CH3CH2OH + NAD+ → CH3CHO + NADH + H+

This allows the consumption of alcoholic beverages, but its organic process purpose is likely the dislocation of alcohols naturally controlled in foods or produced away bacteria in the alimentary tract.[25]

Some other biological process purpose may be metabolism of the endogenous alcohol vitamin A (vitamin A1), which generates the hormone retinoic acid, although the function here may follow primarily the reasoning by elimination of toxic levels of retinol.[26] [27]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Intoxicant dehydrogenase is also involved in the toxicity of other types of intoxicant: For instance, it oxidizes methanol to produce methanal and ultimately formic acid.[28] Man have at any rate vi slightly different alcohol dehydrogenases. Each is a dimer (i.e., consists of two polypeptides), with for each one dimer containing two zinc ions Zn2+. One of those ions is crucial for the operation of the enzyme: It is located at the catalytic site and holds the hydroxyl group of the alcohol in place.

Alcohol dehydrogenase activenes varies between men and women, betwixt young and old, and among populations from different areas of the world. For example, young women are incapable to process alcohol at the same rate as young men because they coif not verbalize the alcohol dehydrogenase American Samoa highly, although the inverse is true among the old.[29] The level of activity may not atomic number 4 dependent only on level of expression just as wel on allelic variety among the population.

The weak genes that encode sort II, III, IV, and V alcohol dehydrogenases are ADH4, ADH5, ADH7, and ADH6, respectively.

Yeast and bacterium [edit]

Unlike humans, yeast and bacteria (demur lactic acid bacterium, and E. coli in certain conditions) do not ferment glucose to lactate. Instead, they turn it to grain alcohol and CO2 . The whole reaction can be seen below:

- Glucose + 2 ADP + 2 Pi → 2 ethanol + 2 Conscientious objector2 + 2 ATP + 2 H2O[30]

In yeast[31] and many a bacteria, alcohol dehydrogenase plays an important part in fermen: Pyruvate resulting from glycolysis is born-again to acetaldehyde and carbon dioxide, and the acetaldehyde is then reduced to ethanol by an intoxicant dehydrogenase called ADH1. The purpose of this latter step is the regeneration of NAD+, and then that the energy-generating glycolysis can continue. Humans exploit this litigate to produce alcoholic beverages, past letting yeast ferment diverse fruits surgery grains. Barm can acquire and consume their own alcoholic beverage.

The main alcohol dehydrogenase in yeast is bigger than the human one, consisting of four sooner than just two subunits. It also contains zinc at its chemical action site. Together with the zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenases of animals and humans, these enzymes from yeasts and many bacteria phase the family of "chain"-alcohol dehydrogenases.

Brewer's yeast also has other alcohol dehydrogenase, ADH2, which evolved exterior of a replicate version of the chromosome containing the ADH1 gene. ADH2 is used by the barm to exchange ethanol back into acetaldehyde, and it is expressed only when gelt concentration is low. Having these two enzymes allows yeast to produce alcohol when sugar is fruitful (and this alcohol and then kills off competing microbes), so continue with the oxidation of the alcohol erstwhile the sugar, and competitor, is gone.[32]

Plants [edit]

In plants, ADH catalyses the selfsame reaction as in barm and bacteria to ensure that there is a constant render of NAD+. Maize has 2 versions of ADH - ADH1 and ADH2, Arabidopsis thaliana contains only one ADH cistron. The structure of Arabidopsis ADH is 47%-conserved, relative to ADH from horse liver. Structurally and functionally important residues, so much as the seven residues that provide ligands for the chemical action and noncatalytic zinc atoms, however, are preserved, suggesting that the enzymes have a like-minded structure.[33] ADH is constitutively declared at low levels in the roots of young plants grown on agar. If the roots deficiency atomic number 8, the formula of ADH increases importantly.[34] Its expression is also increased in response to dehydration, to low-spirited temperatures, and to abscisic Lucy in the sky with diamonds, and it plays an profound role in fruit ripening, seedlings growing, and pollen evolution.[35] Differences in the sequences of ADH in different species induce been used to create phylogenies showing how closely consanguine different species of plants are.[36] It is an nonpareil gene to use ascribable its convenient size (2–3 kb in length with a ≈1000 nucleotide coding sequence) and low replicate number.[35]

Iron-containing [edit]

| Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

bacillus stearothermophilus glycerol dehydrogenase complex with glycerin | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Fe-ADH | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00465 | ||||||||

| Pfam tribe | CL0224 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001670 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00059 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1jqa / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

A tierce family of inebriant dehydrogenases, unrelated to the to a higher place two, are iron-containing ones. They occur in bacteria and fungi. In compare to enzymes the higher up families, these enzymes are oxygen-sensitive.[ citation needful ] Members of the iron-containing intoxicant dehydrogenase kinsperson include:

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (gene ADH4)[37]

- Zymomonas mobilis intoxicant dehydrogenase 2 (gene adhB)[38]

- Escherichia coli propanediol oxidoreductase EC 1.1.1.77 (gene fucO),[39] an enzyme involved in the metabolism of fucose and which also seems to contain ferrous ion(s).

- Clostridium acetobutylicum NADPH- and NADH-unfree butanol dehydrogenases EC 1.1.1.- (genes adh1, bdhA and bdhB),[40] enzymes that have activity using butanol and grain alcohol as substrates.

- E. coli adhE,[41] an iron-dependent enzyme that harbours three different activities: alcohol dehydrogenase, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating) EC 1.2.1.10 and pyruvate-formate-lyase deactivase.

- Bacterial glycerol dehydrogenase EC 1.1.1.6 (gene gldA or dhaD).[42]

- Clostridium kluyveri NAD-dependent 4-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (4hbd) EC 1.1.1.61

- Citrobacter freundii and Klebsiella pneumoniae 1,3-propylene glycol dehydrogenase Common Market 1.1.1.202 (gene dhaT)

- Bacillus methanolicus NAD-dependent wood alcohol dehydrogenase EC 1.1.1.244[43]

- E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium ethanolamine utilization protein eutG.

- E. coli hypothetical protein yiaY.

Other types [redact]

A further class of alcohol dehydrogenases belongs to quinoenzymes and requires quinoid cofactors (e.g., pyrroloquinoline benzoquinone, PQQ) as enzyme-bound electron acceptors. A typical object lesson for this type of enzyme is methyl alcohol dehydrogenase of methylotrophic bacteria.

Applications [edit]

In biotransformation, alcohol dehydrogenases are often used for the synthesis of enantiomerically pure stereoisomers of chiral alcohols. Often, high chemo- and enantioselectivity can Be achieved. Single exemplar is the alcohol dehydrogenase from Lactobacillus brevis (LbADH), which is represented to be a variable biocatalyst.[44] The high chemospecificity has been addicted also in the case of substrates presenting two potential redox sites. E.g. cinnamaldehyde presents both open-chain double bond and aldehyde use. Unlike conventional catalysts, alcohol dehydrogenases are capable to by selection act solitary on the latter, yielding exclusively cinnamyl alcohol.[45]

In fuel cells, alcohol dehydrogenases can be used to catalyze the breakdown of fire for an ethanol fuel cell. Scientists at Saint Louis University have put-upon carbon paper-supported alcohol dehydrogenase with poly(methylene green) atomic number 3 an anode, with a nafion tissue layer, to achieve about 50 μA/cm2.[46]

In 1949, E. Racker defined one unit of intoxicant dehydrogenase activity as the sum that causes a exchange in optical density of 0.001 per minute under the standard conditions of attempt.[47] Recently, the international definition of enzymatic social unit (E.U.) has been more park: one unit of Inebriant Dehydrogenase bequeath convert 1.0 μmole of grain alcohol to acetaldehyde per minute at pH 8.8 at 25 °C.[48]

Clinical import [edit]

Alcoholism [blue-pencil]

There have been studies exhibit that variations in ADH that influence fermentation alcohol metabolism have an impact on the risk of inebriant dependence.[8] [9] [10] [11] [49] The strongest result is attributable variations in ADH1B that increase the rate at which alcohol is regenerate to acetaldehyde. One such variant is near shared in individuals from East Asia and the Middle East, another is most common in individuals from Africa.[9] Both variants reduce the risk for drunkenness, merely individuals can become alcoholic despite that. Researchers have tentatively detected a few other genes to be associated with alcoholism, and know that there must be many more remaining to be found.[50] Research continues in order to key out the genes and their act upon connected drunkenness.

Do drugs dependance [edit]

Drug addiction is another problem related to with ADH, which researchers think power be linked to dipsomania. One particular study suggests that drug dependence has sevener ADH genes associated with it, notwithstandin, more inquiry is necessary.[51] Alcohol dependence and other drug dependence may share some put on the line factors, but because intoxicant addiction is often comorbid with otherwise drug dependences, the association of ADH with the other drug dependencies English hawthorn non live causal.

Poisoning [edit]

Fomepizole, a drug that competitively inhibits alcohol dehydrogenase, can be used in the setting of acute methanol[52] or glycol[53] toxicity. This prevents the conversion of the wood spirit or glycol to its toxic metabolites (such as formic acid, formaldehyde, Oregon glycolate). The same impression is also sometimes achieved with ethanol, again by capitalist inhibition of Vasopressin.

Dose metabolic process [edit]

The drug hydroxyzine is incomplete into its active metabolite cetirizine by alcohol dehydrogenase. Other drugs with alcoholic beverage groups may be metabolized in a suchlike way atomic number 3 long as steric hindrance does not prevent the alcohol from reaching the active site.[54]

See too [edit]

- Alcohol dehydrogenase (NAD(P)+)

- Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- Oxidoreductase

- Blood alcohol placid for rates of metastasis

References [delete]

- ^ PDB: 1m6h; Sanghani PC, Robinson H, Bosron WF, Hurley TD (September 2002). "Weak glutathione-drug-addicted methanal dehydrogenase. Structures of apo, binary, and inhibitory trio complexes". Biochemistry. 41 (35): 10778–86. doi:10.1021/bi0257639. PMID 12196016.

- ^ Gutheil WG, Holmquist B, Vallee BL (January 1992). "Purification, picture, and partial sequence of the glutathione-leechlike methanal dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli: a class III alcohol dehydrogenase". Biochemistry. 31 (2): 475–81. doi:10.1021/bi00117a025. PMID 1731906.

- ^ a b Danielsson O, Jörnvall H (October 1992). ""Enzymogenesis": classic liver alcohol dehydrogenase origination from the glutathione-subject formaldehyde dehydrogenase line". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US. 89 (19): 9247–51. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.9247D. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.19.9247. PMC50103. PMID 1409630.

- ^ a b

- ^ Staab CA, Hellgren M, Höög JO (December 2008). "Medium- and curtly-chain dehydrogenase/reductase cistron and protein families : Dual functions of alcoholic beverage dehydrogenase 3: implications with nidus connected formaldehyde dehydrogenase and S-nitrosoglutathione reductase activities". Cancellated and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (24): 3950–60. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8592-2. PMID 19011746. S2CID 8574022.

- ^ Godoy L, Gonzàlez-Duarte R, Albalat R (2006). "S-Nitrosogluthathione reductase activity of lancelet ADH3: insights into the nitric oxide metabolism". International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2 (3): 117–24. DoI:10.7150/ijbs.2.117. PMC1458435. PMID 16763671.

- ^ a b c d Whitfield, John B (1994). "Antidiuretic hormone and ALDH genotypes in sex act to alcohol biological process rate and sensitivity" (PDF). Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2: 59–65. PMID 8974317. [ permanent breathless link ]

- ^ a b Thomasson HR, Edenberg HJ, Crabb DW, Mai Forty, Jerome RE, Li TK, Wang SP, Lin YT, Lu Rb, Yin SJ (April 1991). "Alcoholic beverage and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes and alcoholism in Taiwanese men". American Daybook of Hominid Genetics. 48 (4): 677–81. PMC1682953. PMID 2014795.

- ^ a b c Edenberg HJ, McClintick JN (October 2018). "Alcohol dehydrogenases, aldehyde dehydrogenases and alcohol use disorders: a critical follow-up". Inebriation, Clinical and Experimental Research. 42 (12): 2281–2297. doi:10.1111/genus Acer.13904. PMC6286250. PMID 30320893.

- ^ a b Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ (2012). "Genes encoding enzymes involved in grain alcohol metabolism". Alcohol Research. 34 (3): 339–44. PMC3756590. PMID 23134050.

- ^ a b Walters RK, Polimanti R, Johnson EC, McClintick JN, Adams MJ, Adkins AE, et al. (December 2018). "Transancestral GWAS of alcohol dependence reveals common genetic underpinnings with psychiatric disorders". Nature Neuroscience. 21 (12): 1656–1669. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0275-1. PMC6430207. PMID 30482948.

- ^ a b c d Peng Y, Shi H, Qi XB, Xiao CJ, Zhong H, Ma RL, Su B (January 2010). "The ADH1B Arg47His polymorphism in east Asian populations and expansion of rice domestication in history". BMC Biological process Biology. 10: 15. Interior Department:10.1186/1471-2148-10-15. PMC2823730. PMID 20089146.

- ^ Eng MY (1 January 2007). "Alcoholic beverage Research and Health". Alcoholic beverage Health & Research World. U.S. Government Printing process Office. ISSN 1535-7414.

- ^ Negelein E, Wulff HJ (1937). "Diphosphopyridinproteid ackohol, acetaldehyd". Biochem. Z. 293: 351.

- ^ Theorell H, McKEE JS (October 1961). "Mechanics of action of liver intoxicant dehydrogenase". Nature. 192 (4797): 47–50. Bibcode:1961Natur.192...47T. Department of the Interior:10.1038/192047a0. PMID 13920552. S2CID 19199733.

- ^ Jörnvall H, Harris JI (April 1970). "Sawbuck liver alcohol dehydrogenase. On the primary structure of the ethanol-active isoenzyme". European Diary of Biochemistry. 13 (3): 565–76. Department of the Interior:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00962.x. PMID 5462776.

- ^ Brändén CI, Eklund H, Nordström B, Boiwe T, Söderlund G, Zeppezauer E, Ohlsson I, Akeson A (August 1973). "Structure of liver alcohol dehydrogenase at 2.9-angstrom unit resolution". Transactions of the National Academy of Sciences of the US of America. 70 (8): 2439–42. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.2439B. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.8.2439. PMC433752. PMID 4365379.

- ^ Hellgren M (2009). Enzymatic studies of alcoholic beverage dehydrogenase by a compounding of in vitro and in silico methods, PhD dissertation (PDF). Stockholm, Sweden: Karolinska Institutet. p. 70. ISBN978-91-7409-567-8.

- ^ a b Sofer W, Martin PF (1987). "Analysis of alcohol dehydrogenase gene expression in Drosophila". One-year Review of Genetic science. 21: 203–25. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.21.120187.001223. PMID 3327463.

- ^ a b c Hammes-Schiffer S, Benkovic SJ (2006). "Relating protein motion to catalysis". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 75: 519–41. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142800. PMID 16756501.

- ^ Willy Brandt EG, Hellgren M, Brinck T, Ingmar Bergman T, Edholm O (February 2009). "Unit dynamics study of zinc binding to cysteines in a peptide mimic of the alcohol dehydrogenase structural atomic number 30 site". Physical Chemistry Stuff Physical science. 11 (6): 975–83. Bibcode:2009PCCP...11..975B. doi:10.1039/b815482a. PMID 19177216.

- ^ Sultatos LG, Pastino GM, Rosenfeld CA, Flynn EJ (March 2004). "Incorporation of the transmissible control of intoxicant dehydrogenase into a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for ethanol in humans". Toxicological Sciences. 78 (1): 20–31. Interior Department:10.1093/toxsci/kfh057. PMID 14718645.

- ^ Edenberg HJ, McClintick JN (December 2018). "Alcoholic beverage Dehydrogenases, Aldehyde Dehydrogenases, and Alcohol Use Disorders: A Critical Critique". Alcoholism, Objective and Experimental Research. 42 (12): 2281–2297. doi:10.1111/acer.13904. PMC6286250. PMID 30320893.

- ^ Farrés J, Moreno A, Crosas B, Peralba JM, Allali-Hassani A, Hjelmqvist L, et al. (September 1994). "Alcohol dehydrogenase of class IV (sigma sigma-ADH) from human stomach. cDNA chronological succession and structure/function relationships". Continent Journal of Biochemistry. 224 (2): 549–57. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00549.x. PMID 7925371.

- ^ Kovacs B, Stöppler MC. "Intoxicant and Victual". MedicineNet, Inc. Archived from the original connected 23 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ Duester G (September 2008). "Retinoic superman deductive reasoning and signaling during early organogenesis". Cell. 134 (6): 921–31. DoI:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. PMC2632951. PMID 18805086.

- ^ Hellgren M, Strömberg P, Gallego O, Martras S, Farrés J, Persson B, Parés X, Höög JO (February 2007). "Alcohol dehydrogenase 2 is a starring hepatic enzyme for human retinol metabolism". Cellular and Building block Life Sciences. 64 (4): 498–505. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-6449-8. PMID 17279314. S2CID 21612648.

- ^ Ashurst JV, Nappe TM (2020). "Wood spirit Toxicity". StatPearls. Hold dear Island (FL): StatPearls Publication. PMID 29489213. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Parlesak A, Billinger MH, Bode C, Bode JC (2002). "Stomachal alcohol dehydrogenase activity in man: influence of sexuality, age, alcohol consumption and smoke in a caucasian population". Alcohol and Dipsomania. 37 (4): 388–93. doi:10.1093/alcalc/37.4.388. PMID 12107043.

- ^ Cox M, Nelson DR, Lehninger Alabama (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry . San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. p. 180. ISBN978-0-7167-4339-2.

- ^ Leskovac V, Trivić S, Pericin D (December 2002). "The three zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenases from baker's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae". FEMS Yeast Research. 2 (4): 481–94. doi:10.1111/j.1567-1364.2002.tb00116.x. PMID 12702265.

- ^ Coghlan A (23 December 2006). "Festive special: The beer maker's tarradiddle - living". New Scientist. Archived from the master copy on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Yangtze Kiang C, Meyerowitz Pica (March 1986). "Molecular cloning and DNA sequence of the Arabidopsis thaliana alcohol dehydrogenase factor". Legal proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (5): 1408–12. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.1408C. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.5.1408. PMC323085. PMID 2937058.

- ^ Chung HJ, Ferl RJ (October 1999). "Arabidopsis alcohol dehydrogenase expression in both shoots and roots is conditioned by root growth environment". Plant Physiology. 121 (2): 429–36. doi:10.1104/pp.121.2.429. PMC59405. PMID 10517834.

- ^ a b Thompson C.E., Fernandes CL, de Souza ON, de Freitas LB, Salzano FM (May 2010). "Evaluation of the impact of functional variegation on Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Fabaceae, and Pinaceae alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes". Journal of Molecular Modeling. 16 (5): 919–28. doi:10.1007/s00894-009-0576-0. PMID 19834749. S2CID 24730389.

- ^ Järvinen P, Palmé A, Orlando Morales L, Lännenpää M, Keinänen M, Sopanen T, Lascoux M (November 2004). "Phylogenetic relationships of Betula species (Betulaceae) based on nuclear Pitressin and chloroplast matK sequences". American Daybook of Vegetation. 91 (11): 1834–45. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.11.1834. PMID 21652331. Archived from the original happening 26 May 2010.

- ^ Williamson VM, Paquin CE (September 1987). "Homology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADH4 to an iron-excited alcohol dehydrogenase from Zymomonas mobilis". Molecular & General Genetic science. 209 (2): 374–81. doi:10.1007/bf00329668. PMID 2823079. S2CID 22397371.

- ^ Conway T, Sewell GW, Osman YA, Ingram LO (June 1987). "Cloning and sequencing of the alcohol dehydrogenase II gene from Zymomonas mobilis". Journal of Bacteriology. 169 (6): 2591–7. doi:10.1128/jb.169.6.2591-2597.1987. PMC212129. PMID 3584063.

- ^ Conway T, Ingram LO (July 1989). "Law of similarity of Escherichia coli propanediol oxidoreductase (fucO product) and an unusual alcohol dehydrogenase from Zymomonas mobilis and Genus Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Journal of Bacteriology. 171 (7): 3754–9. doi:10.1128/jb.171.7.3754-3759.1989. PMC210121. PMID 2661535.

- ^ Walter KA, Bennett GN, Papoutsakis ET (November 1992). "Molecular characterization of two Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 butyl alcohol dehydrogenase isozyme genes". Journal of Bacteriology. 174 (22): 7149–58. doi:10.1128/jb.174.22.7149-7158.1992. PMC207405. PMID 1385386.

- ^ Kessler D, Leibrecht I, Knappe J (April 1991). "Pyruvate-formate-lyase-deactivase and acetyl-CoA reductase activities of Escherichia coli reside on a polymeric protein particle encoded by adhE". FEBS Letters. 281 (1–2): 59–63. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)80358-A. PMID 2015910. S2CID 22541869.

- ^ Truniger V, Boos W (March 1994). "Mapping and cloning of gldA, the structural gene of the Escherichia coli glycerin dehydrogenase". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (6): 1796–800. doi:10.1128/jb.176.6.1796-1800.1994. PMC205274. PMID 8132480.

- ^ deVries GE, Arfman N, Terpstra P, Dijkhuizen L (August 1992). "Cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of the Bacillus methanolicus C1 methanol dehydrogenase gene". Journal of Bacteriology. 174 (16): 5346–53. DoI:10.1128/jb.174.16.5346-5353.1992. PMC206372. PMID 1644761.

- ^ Leuchs S, Greiner L (2011). "Intoxicant dehydrogenase from Lactobacillus brevis: A variable catalyst for enenatioselective step-dow" (PDF). CABEQ: 267–281. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Zucca P, Littarru M, Rescigno A, Sanjust E (May 2009). "Cofactor recycling for exclusive catalyst biotransformation of cinnamaldehyde to cinnamyl alcohol". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 73 (5): 1224–6. doi:10.1271/bbb.90025. PMID 19420690. S2CID 28741979.

- ^ Moore CM, Minteer SD, Martin RS (February 2005). "Microchip-founded ethanol/O biofuel cell". Lab happening a Chip. 5 (2): 218–25. doi:10.1039/b412719f. PMID 15672138.

- ^ Racker E (May 1950). "Crystalline alcohol dehydrogenase from baker's yeast". The Diary of Biological Chemistry. 184 (1): 313–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)51151-6. PMID 15443900.

- ^ "Enzymatic Assay of Alcohol Dehydrogenase (Common Market 1.1.1.1)". Sigma Aldrich. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Sanchez-Roige S, Arnold Daniel Palmer AA, Fontanillas P, Elson SL, Adams MJ, Howard DM, et al. (February 2019). "Genome-Opened Association Contemplate Meta-Psychoanalysis of the Alcohol Use Disorders Recognition Test (AUDIT) in Two Universe-Based Cohorts". The American Diary of Psychological medicine. 176 (2): 107–118. Interior Department:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18040369. PMC6365681. PMID 30336701.

- ^ Kranzler Hour, Zhou H, Kember RL, Vickers Smith R, Justice AC, Damrauer S, et al. (April 2019). "Genome-wide tie study of alcohol consumption and use disorder in 274,424 individuals from octuple populations". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1499. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1499K. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09480-8. PMC6445072. PMID 30940813.

- ^ Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Schork NJ, Gelernter J (February 2007). "Treble Vasopressin genes modulate risk of exposure for drug dependence in both African- and European-Americans". Human Building block Genetics. 16 (4): 380–90. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl460. PMC1853246. PMID 17185388.

- ^ International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS): Wood alcohol (PIM 335), [1], retrieved on 1 March 2008

- ^ Velez LI, Shepherd G, Lee YC, Keyes DC (September 2007). "Ethylene glycol ingestion processed simply with fomepizole". Diary of Medical Toxicology. 3 (3): 125–8. doi:10.1007/BF03160922. PMC3550067. PMID 18072148.

- ^ Nelson W (2013). "Chapter 36: Nonsteroidal anti-provocative drugs". In Foye WO, Lemke TL, Williams DA (EDS.). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemical science (7th ED.). City of Brotherly Love: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN978-1-60913-345-0.

External links [edit]

- PDBsum has links to three-dimensional structures of various alcohol dehydrogenases contained in the Protein Information Bank

- ExPASy contains golf links to the alcohol dehydrogenase sequences in Swiss-Prot, to a MEDLINE literature search most the enzyme, and to entries in other databases.

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the complex body part info available in the PDB for Alcohol dehydrogenase 1A.

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the anatomical structure information available in the PDB for Alcohol dehydrogenase 1B.

- PDBe-Kilobyte provides an overview of all the structure data available in the PDB for Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C.

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of altogether the structure information free in the PDB for Alcohol dehydrogenase 4.

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Intoxicant dehydrogenase sort-3.

Where Is Alcohol Dehydrogenase Found in the Cell

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcohol_dehydrogenase

0 Response to "Where Is Alcohol Dehydrogenase Found in the Cell"

Post a Comment